MARTYRDOM is one of seven basic character flaws or “dark” personality traits. We all have the potential for feeling victimised, but in people with a strong fear of worthlessness, Martyrdom can become a dominant pattern. the term is sometimes used to describe someone who seems to always be suffering in one way or another. Individuals with martyrdom complex might always have a story about their latest woe or a sacrifice they’ve made for someone else. They might even exaggerate bad things that happen to get sympathy or make others feel guilty.

Is it the same thing as a victim mentality?

A martyr complex can seem very similar to a victim mentality. Both tend to be more common in survivors of abuse or other trauma, especially those who don’t have access to adequate coping tools.

But the two mindsets do have some subtle distinctions.

A person with a victim mentality typically feels personally victimized by anything that goes wrong, even when the problem, rude behavior, or mishap wasn’t directed at them.

They may not show much interest in hearing possible solutions. Instead, they might give the impression of just wanting to wallow in misery.

A martyr complex goes beyond this. People with a martyr complex don’t just feel victimized. They typically seem to go out of their way to find situations that are likely to cause distress or other suffering.

According to Sharon Martin, LCSW, someone with a martyr complex “sacrifices their own needs and wants in order to do things for others.” She adds that they “don’t help with a joyful heart but do so out of obligation or guilt.”

She goes on to explain this can breed anger, resentment, and a sense of powerlessness. Over time, these feelings can make a person feel trapped, without an option to say no or do things for themselves.

What does it look like?

Someone who always seems to be suffering — and appears to like it that way — could have a martyr complex, according to Lynn Somerstein, PhD. This pattern of suffering can result in emotional or physical pain and distress.

Here’s a look at some other signs that you or someone else may have a martyr complex.

You do things for people even though you don’t feel appreciated

Wanting to help those closest to you suggests you have a kind and compassionate nature. You may do these things just to help out, not because you want loved ones to recognize your efforts or the sacrifices you’ve made for their sake.

But when does helping out suggest a martyr complex?

Many people who are bothered by a lack of appreciation will simply stop helping out. If you have martyr tendencies, however, you might continue to offer support while expressing your bitterness by complaining, internally or to others, about the lack of appreciation.

Martyrdom in History

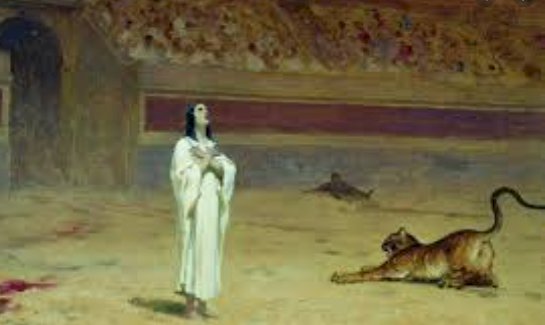

Martyrdom traditionally refers to an experience of suffering persecution, torture and death on account of one’s faith.

Before exploring martyrdom as a psychological mechanism, it is worth understanding martyrdom in this more traditional sense — though it turns out that the two aren’t really that different.

Martyrdom is a familiar concept in the history of religion. In the ancient world, for example, many Christians were hunted down and cruelly tortured to death by their Roman rulers, simply for being Christians. Faithful survivors would then refer to their executed comrades as martyrs (from the Greek mártys, meaning “witness”). And if their comrades had stayed true to the faith despite all the suffering, then they might also be referred to as saints, meaning outstandingly holy individuals.

The careful use of words can put a specific slant on a situation, shaping how it is represented in the minds of others, as well as in our own minds. A word like martyrdom, for example, helps to separate “us” from “them” in terms of morality.

Having martyrs in our ranks implies that we are fundamentally innocent victims while they are fundamentally evil oppressors. It lets the oppressors know that they are committing an offense against God. It also serves as an inspiration to the faithful, contrasting the goodness and righteousness of the innocent underdog with the unholy injustice of an evil empire.

Once the power of influencing perceptions is understood, martyrdom can also be sought deliberately for propaganda purposes, rather than simply endured as unjust cruelty.

Martyrdom as a Deliberate Stunt

Originally, martyrdom was about keeping the faith while facing an unwanted early death:

“You may kill my body, but my faith will never die.”

But often, consciously or unconsciously, this has changed. In fact, committing a spectacular suicide as a sign of religious or political injustice seems like a worthwhile ambition to some.

For individuals with no strong attachment to life, choosing to become a martyr (in the name of Islam, say) — and taking out a few non-believers at the same time — can seem an extremely noble and attractive way to go. Not only does your willingness to die for your beliefs create “shock and awe” in the oppressors, but you also get to be feted in your own community (albeit posthumously)—and your family will be well honoured—and you are promised special treatment by the Almighty in the afterlife.

The Koran prohibits suicide, religious scholars say. But some Muslim groups insist that by classifying the bombers as martyrs, their self-destruction becomes permissible because it is a form of self-sacrifice, and because it is honorable to die in battle against infidels.

Despite the fact that most religious persons (including Muslims) do not consider suicidal acts of terror to be valid cases of martyrdom, the term is used routinely by those using it as a form of propaganda. A would-be suicide bomber describing himself as a “martyr” clearly wants to imply that he is on the side of the innocent oppressed.

This suicide-as-propaganda-stunt — acting out the role of outraged innocent victim as a form of “narrative attack” on others’ minds — is a far cry from the idea of keeping the faith despite torture and execution. Yet this is the very essence of martyrdom as a psychological syndrome or character flaw: the martyr complex.

The Martyr Complex

In the psychological sense, a person with a martyr complex is one who routinely talks about, emphasizes, exaggerates and even creates his own suffering in an attempt to make someone else appear guilty and blameworthy. Again and again and again.

Martyrdom is a sort of implosion of the will. The subconscious message that martyrdom puts out is something like:

“I have no will of my own because you are constantly oppressing me, denying me my freedom. All problems in my life are caused by your unjust mistreatment of me.”

Instead of exercising their personal power, an individual with overwhelming martyrdom will persistently act as though their power had been deliberately taken away from them.

In more mature versions, the individual may be conscious of their martyrdom streak and try to turn it into something positive, such as publicly suffering for a worthy social cause.

Famous examples of individuals with a chief feature of martyrdom include:

- Joan of Arc

- Martin Luther King

- Jimmy Swaggart

- Yoko Ono

- Nelson Mandela

Positive and Negative Poles

In the case of martyrdom, the positive pole is termed SELFLESSNESS and the negative pole is termed MORTIFICATION.

| MARTYRDOM | ||

| negative pole | ←→ | positive pole |

| MORTIFICATION | SELFLESSNESS | |

“Mortification“, which literally means “putting to death”, refers to self-inflicted suffering and torment. In this negative pole, there is a distorted (subconscious) belief that tremendous suffering is necessary, whether privately to atone for one’s sins or publicly to attract sympathy and pin the blame on others.

The individual will be unconsciously compelled to experience situations in which they are apparently victimised, mistreated and persecuted. Some will even go so far as to die to prove their point (“Behold my terrible fate, which is all your fault”).

“Selflessness” refers to a conscious willingness to put others’ needs and wants first. Ideally, this is out of choice rather than just a performance, which is more often the case with martyrdom.

If an individual with a streak of martyrdom is relatively self-aware and in control of their fears, their martyrdom can manifest in a more relaxed way as selfless commitment to what they see as a good cause.

Components of Martyrdom

Like all negative patterns of personality, martyrdom involves the following components:

- Early negative experiences

- Misconceptions about the nature of self, life or others

- A constant fear and sense of insecurity

- A maladaptive strategy to protect the self

- A persona to hide all of the above in adulthood

Early Negative Experiences

In the case of martyrdom, the key negative experiences in childhood revolve around blame, victimisation, and being unable to do anything right in the eyes of the parents. Typically, the child is constantly punished for getting it wrong, and constantly blamed for whatever goes wrong. He might even be portrayed, unfairly, as the source of all of the parents’ problems.

For example, the child’s parents might blame the child for getting sick when times are already hard enough. Or the parents might be intolerant of displays of anger, and regularly punish the child for showing the slightest hint of it—all of which merely breeds more outrage and resentment.

This constant blaming and unreasonably punitive treatment might also contrast sharply with, say, how an older sibling is treated, or how other kids at school are treated by their own parents. For example, the child might have an older brother who can get away with anything, while she gets blamed even for the brother’s bad behaviour.

Misconceptions

Getting the love, care and attention which all children naturally crave seems to be an impossible task in this kind of setup.

If I just do as I please, I get punished.

If anything goes wrong, anywhere, I get blamed for it.

Whenever I express myself or assert myself I am rejected.

Whatever is going wrong, it is all supposedly the child’s fault. It is as if the child has no place in the family—in fact, no place in the world.

Over time, if such experiences of unfair disapproval and oppression are fairly constant, the child comes to perceive others, or at least certain types of others such as authority figures, as fundamentally cruel and unfair.

Fear

Following these bad experiences and negative perceptions, the child also becomes gripped by a specific kind of fear. In this case, the fear is of their own worthlessness—being of no value to anyone, being nothing but trouble, being a terrible mistake.

The child experiences a tension between believing that he is fundamentally worthless and feeling that he is always being unfairly blamed and punished. His worst fear is that all the blame he receives is valid—he really is to blame for everything (after all, like all normal kids, he knows he is to blame for some things).

What if it’s true—that it is all my fault? That everything I do is bad, know matter how hard I try to be good? Then my life serves no purpose. I am worse than useless.

Strategy

The basic strategy for coping with this constant fear of unbearable worthlessness is to twofold:

1. Seek justice and vengeance against wrong-doers.

2. Seek reassuring confirmations of one’s innocence and worth once and for all.

To do this, the martyr subconsciously attracts and sets up nasty problems for himself for which others can take the blame. He lurches from one horrible situation to the next. Within these situations, not only can he attract sympathy as an innocent victim, but also he can finally, indirectly, express the anger for his original mistreatment.

Persona

The outer mask of martyrdom is all about being the innocent victim. Typically this involves:

- constantly moaning, griping, complaining, talking about one’s problems;

- exaggerating one’s level of suffering, hardship, etc.;

- avoiding any form of relief, including therapy, lest it end the all-important suffering.

A person with a chief feature of martyrdom has a habit of complaining about endless problems and blaming those problems on anyone or anything but himself. It’s all the fault of his mother, his boss, his so-called friends, this society, the government, people in general, life, God.

Blaming others or the world at large is a way of soliciting sympathy and avoiding the dreadful inner feeling of worthlessness. It is as if the martyr is saying to the world, “Look how much I am suffering, and through no fault of my own! Please sympathise with me and tell me it’s not my fault!”

For martyrs, the idea of taking responsibility for improving or correcting their own lives is anathema. All negative personality patterns are like stuck records, and this one is stuck in a perpetual state of victimization. To end the suffering would scupper any chance of having the mistreatment acknowledged and all wrong-doers finally exposed.

It is important, though, that the suffering be seen as anything but self-inflicted or exaggerated. Hence, the martyr will outwardly deny any responsibility for his own suffering, and always exaggerate the role played by others. The martyr will also over-stress that his own motives are entirely pure—”I was only trying to help when suddenly he lashed out at me for no reason!”

Handling Martyrdom

Like all negative traits, martyrdom is a vicious circle. It simply creates the very experiences which the individual wants to avoid.

Those with martyrdom will find myriad ways to “tempt fate” in order to do something that will establish their worth once and for all. Martyrdom can attract thankless families, wasting diseases, sabotaged careers, destructive personal relationships, in an almost constant search for the elusive “grail” of worthiness.

MICHAEL

All people are capable of this kind of behaviour. It is when it subconsciously dominates someone’s personality, however, that they are said to have a chief feature of martyrdom.

The solution to martyrdom lies in:

- being honest with oneself about using martyrdom

- giving up complaining, blaming and the attachment to being right

- giving up the attachment to victimisation and suffering

- allowing more pleasure, and being willing to be seen enjoying life

- taking responsibility for one’s choices

- learning to say ‘no’ to others

In short, it means swinging to the positive pole of impatience, which is ‘audacity’.

Thank you for sharing superb informations. Your web site is so cool. I’m impressed by the details that you have on this site. It reveals how nicely you perceive this subject. Bookmarked this web page, will come back for extra articles. You, my friend, ROCK! I found simply the information I already searched all over the place and simply could not come across. What a perfect web site.