SELF-DESTRUCTION is one of seven basic character flaws or “dark” personality traits. We all have the potential for self-destructive tendencies, but in people with a strong fear of losing self-control, Self-Destruction can become a dominant pattern. As previously discussed in our article on character flaws: the seven chief features of ego, one of the chief features of ego is self-destruction.

What Is Self-Destruction?

Self destruction is usually defined as “The voluntary destruction of something by itself.”

In human personality terms, we are really talking about counter-productive and self-defeating habits which deny oneself happiness but can instead cause pain, either deliberately or inadvertently. Self-destruction in the literal sense of suicide is the most extreme form. Mostly, however, it is more subtle, such as repeatedly committing “professional suicide”. It’s an umbrella term for a variety of self-damaging patterns, from doing things that always seem to backfire, to habitual self-harm, to crazy recklessness.

You’ve probably done something self-destructive at some point. Just about everyone has. Most of the time, it’s not intentional and doesn’t become a habit.

Self-destructive behaviors are those that are bound to harm you physically or mentally. It may be unintentional. Or, it may be that you know exactly what you’re doing, but the urge is too strong to control.

It may be due to earlier life experiences. It can also be related to a mental health condition, such as depression or anxiety.

Read on as we look at some self-destructive behaviors, how to recognize them, and what to do about them.

What is self-destructive behavior?

Self-destructive behavior is when you do something that’s sure to cause self-harm, whether it’s emotional or physical. Some self-destructive behavior is more obvious, such as:

- attempting suicide

- binge eating

- compulsive activities like gambling, gaming, or shopping

- impulsive and risky sexual behavior

- overusing alcohol and drugs

- self-injury, such as cutting, hair pulling, burning

There are also more subtle forms of self-sabotage. You may not realize you’re doing it, at least on a conscious level. Examples of this are:

- being self-derogatory, insisting you’re not smart, capable, or attractive enough

- changing yourself to please others

- clinging to someone who is not interested in you

- engaging winstrol dosage for definition in alienating or aggressive behavior that pushes people away

- maladaptive behaviors, such as chronic avoidance, procrastination, and passive-aggressiveness

- wallowing in self-pity

The frequency and severity of these behaviors vary from person to person. For some, they’re infrequent and mild. For others, they’re frequent and dangerous. But they always cause problems.

What are common risk factors for self-destructive behavior?

You might be more prone to behave in a self-destructive manner if you’ve experienced:

- alcohol or drug use

- childhood trauma, neglect, or abandonment

- emotional or physical abuse

- friends who self-injure

- low self-esteem

- social isolation, exclusion

If you have one self-destructive behavior, it may the likelihood of developing another

Despicable Me

As with the opposite trait of greed, self-destruction represents a dysfunction in a person’s fundamental relationship with life. A person with greed fears that something vital is lacking or missing from life, and so constantly needs to have more. A person with self-destruction, in contrast, feels that something fundamentally bad or toxic is consuming their life, and needs to keep this under strict control.

For example, there may be part of oneself that once suffered unbearable abuse or damage, perhaps way back in childhood. To revisit this part of the self is just too painful and scary.

Moreover, an anxious young person may think to themselves: “There must be something about me that provoked or attracted or deserved such treatment, for why else would it have happened?” To give expression to this part of oneself once more could simply cause the same traumatic experiences to happen again. For example, Being pretty is what caused this, so I must never look pretty again.

Another good name for self-destruction could be self-denial. There is a splitting of the personality in which this “thing in me” is to be ignored and suppressed by any means possible, at whatever cost. The person feels that their very being must be kept under strict control.

Varieties of Self-Destruction

Again, the urge to “self-destruct” need not be literal or physical. In fact, there is a spectrum of self-destructive behaviours, from mild to risky to fatal.

The most widespread forms of self-destructive behaviour are eating disorders, alcohol abuse, drug abuse and compulsive gambling. Self-destruction can also take the form of self-sabotage or self-defeating behaviours—continually doing things which are bound to lead to one’s own failure or downfall.

Deliberate self-injury is surprisingly common in young people worldwide. It has also been linked with borderline personality disorder in adulthood, a chronic and difficult to treat condition characterized by impulsive behaviours, unstable mood swings and a tendency towards suicide. In fact, self-injurers are about 75 times more likely to kill themselves.

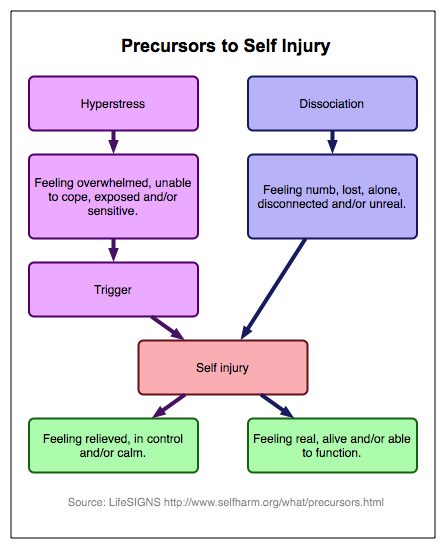

Researchers have discovered a common pattern in such behaviour (see the diagram Precursors to Self Injury, below). The trigger (or “final straw”) is often a threat of separation, rejection or disappointment in life. This adds to feelings of overwhelming tension, isolation, self-hatred, and apprehension about being unable to control one’s own emotions. The increasing anxiety culminates in a frightening sense of unreality and emptiness that ultimately produces an emotional numbness or depersonalization.

Self-injury is usually a primitive way of coping with the emotional numbness. It is as if, by replacing one’s emotional pain with a physical one, life becomes more bearable. It is also easier to demonstrate that one is in pain when the injury is visible and physical rather than “just psychological”.

Famous Examples

Fiona Apple (b. 1977) is a Grammy-winning American singer-songwriter. At the age of twelve, Fiona was raped on her way home from school.

For years she continued to have nightmares. She would also check her closets to make sure no one was hiding in the house, and would be nervous around older men.

During her teens and the months she spent making her album, Tidal, she suffered with an eating disorder. In a 1998 Rolling Stone interview, she reflected on what this was like:

For me, it wasn’t about being thin, it was about getting rid of the bait attached to my body. A lot of it came from the self-loathing that came from being raped at the point of developing my voluptuousness. I just thought that if you had a body and if you had anything on you that would be grabbed, it would be grabbed. So I did purposely get rid of it.

Other self-destructive figures include:

- Vincent Van Gogh

- Sid Vicious

- Kurt Cobain

- Diana, Princess of Wales

- Michael Jackson

- Marilyn Manson

- Christina Ricci

- Amy Winehouse

- Lindsay Lohan

Note that there is an added complication for self-destructive celebrities. The more they self-harm or take unhealthy risks with their lives, the more attention, controversy, and publicity they generate. As a result, the more successful they become (selling more records or whatever). This merely adds to the vicious circle of self-destruction. It’s as if the entire world wants to know all about the inner demons they are trying to suppress.

Development of Self-Destruction

Like all negative personality traits, self-destruction typically develops through the following sequence:

- Early negative experiences

- Misconceptions about the nature of self, life or others

- A constant fear and sense of insecurity

- A maladaptive strategy to protect the self

- A persona to hide all of the above in adulthood

Early Negative Experiences

In the case of self-destruction, the early negative experiences typically consist of a childhood abuse or trauma over which the child had no control. This kicks off the self-destructive behaviour, while lack of secure parental attachment helps maintain it.

Perhaps the father was a drunk who came home every night in a violent rage. Perhaps the mother was mentally unstable and would attack her children for no apparent reason. Or perhaps school teachers imposed a severe regime involving random punishments. The key factor leading to a self-destructive pattern is the child’s inability to control the onslaught of harm.

In addition, one or both parents may have been unable or unwilling to give the love, care and attention that were naturally craved by the child. So the child would have felt fundamentally alone in this terror, as well as feeling helpless to do anything about it.

Misconceptions

From such experiences of life as harsh, unpredictable and beyond control, the child comes to perceive ‘life’ as a horrible place and ‘self’ as a magnet for pain. Hence:

If life is so cruel then it is not worth living.

I wish I had never been born.

Being hurt so much means that I must be bad. Perhaps I don’t deserve to live.

Fear

Along on such ideas, the child becomes gripped by a complex fear — the fear of losing control. There are all sorts of ways in which this fear manifests —

- losing control of one’s boundaries in intimate relationships;

- losing control of the memory of trauma;

- losing control of whichever part of oneself “attracts” trauma;

- losing control of the urge to destroy that part of oneself once and for all.

In other words, the child is terrified of —

- repeating an earlier trauma,

- expressing whatever part of himself might attract such trauma, and

- unleashing his own desire to punish or eliminate that part of himself.

Those caught in self-destruction are thus embroiled in inner conflict.

Strategy

There are various strategies for coping with this complex issue, but the key is to maintain control of something.

My survival depends upon me taking back control of my life.

One increasingly common route, particularly among adolescent girls, is to take control of eating as a way to “suppress” the physical self. This is the basis of the condition known as anorexia nervosa.

Anxiety compels us to find some sort of self-protection, to feel that there is some way we can control what happens to us. But in many families, especially those with a stifling or oppressive atmosphere, there is simply no room for an anxious child undergoing puberty to exercise control over anything around them. Their very anxiety may be seen as an embarrassment, something to be hidden and never discussed.

So “substitute controls” start to appear, like obsessive-compulsive habits and superstitions. In effect, the need for control turns inwards. It’s like saying, “If I can’t do anything to this family, at least I can do something to myself.”

In many cases, mostly female, a sense of freedom and control is found in the act of eating — or rather, the choice to not eat. The ideal of being stick-thin, free from the desire to eat, seems to tick several boxes at once: “I get to be super-attractive, I feel a sense of personal power, I get a lot of attention from the rest of my family, and they have no way to take back control over my refusing to eat what they give me.”

In a metaphorical way, it’s like saying to the family, “I can’t stomach this any longer.”

Because they actually enjoy feeling some sense of control over their own lives, some self-destructive types will keep testing and pushing their degree of control—How much alcohol can I drink at once? Can I drink even more than the last time? How many drugs can I take and not die? How fast can I drive a motorbike and get away with it?

Every time they survive such an experience, it merely bolsters their belief that control in the face of danger is a necessary strategy. It’s like a superstition — So long as I’m wearing a yellow hat, no bears will eat me. But this false sense of control merely begs the question, prompted by the same fear: Is that the limit of my control? Or can I take an even bigger risk?

The constant need to push the edge of control, plus the fear of losing control and thereby experiencing both powerlessness and pain inside oneself, creates inner conflict and a rising tension which demands to be relieved. Being successful in life in whatever way will only serve to increase the tension, since there is even more need to keep everything bottled up and under control.

The self-destructive person may be therefore caught in a cycle between periods of grim self-control and explosive episodes in which a valve blows and some component of the conflict is set free.

The person is also likely to become addicted to these brief moments of relief, however destructive they may be in the long run.

For example, relief may be found in episodes of binge drinking. A massive dose of alcohol serves as an anaesthetic, eliminating the state of conflict, tension and terror for a while. It does nothing to resolve the basic underlying conflict or pain, however. In fact, the awful consequences of binge drinking merely serve to reinforce the fear of losing control at another level. And yet the brief relief it provides is irresistible to the point of becoming addictive.

All people are capable of this kind of behaviour. When it dominates the personality, however, one is said to have a chief feature of self-destruction.

Persona

Emerging into adulthood, a self-destructive young person probably does not want go around being overtly fearful, conflicted and self-destructive. Hence, the chief feature puts on a public mask which says to the world something like, “Everything’s under control. I only act this way because I want to.” “It’s just a bit of fun.” “I am naturally wild and reckless.” “I’m such a fearless rebel.” In other words, he or she tries to make the behaviour seem positive or cool, rather than a reaction to inner terror.

I think that self-destructiveness can also mean self-reflection, can mean poetic sensibility, it can mean empathy, it can mean a hedonism and a libertarianism and a lack of judgement.

– Courtney Love

Like all chief features of false personality, self-destruction is a vicious circle—only in this case, the end result tends to be fatal. Early intervention is therefore crucial. The real danger is when the person with self-destruction starts to believe their own lie. At that point, the chief feature has won and the most likely outcome is an early death.

Positive and Negative Poles

In the case of self-destruction, the positive pole is termed SACRIFICE and the negative pole is termed IMMOLATION or SUICIDE.

Sacrifice brings the habit of self-destruction under conscious control. It is a willingness to deliberately give up or lose something for a good reason, or for a good cause, rather than out of pure fear.

Sacrifice literally means “make sacred”, in the sense of making an offering to the gods. For example, virtually every primitive society in history has included animal sacrifice as part of its religion. A sacrificial offering can be as cheap and as simple as a flower or a stick of incense. Or it can be as valuable as one’s own life. The more valuable the offering, the greater the sacrifice and the more highly it is regarded.

Today we use sacrifice more generically to describe giving something up, doing without, accepting a minor loss as a way to avoid a greater loss, or in anticipation of later gain. For example, when playing chess we might sacrifice a pawn as a way to avoid losing the game.

A person with a chief feature of self-destruction can at least feel good every now and then about giving something up for the best. For example, instead of automatically sabotaging a new relationship, as is their habit, they can be open about it and offer to drop the relationship from the start, and thereby spare the other person later misery. An honest offering to another is more powerful than insidious self-sabotage.

Immolation also means sacrifice, especially ritual sacrifice by fire, but in this context we are talking about self-sacrifice or suicide.

In the early 1960s, many Vietnamese Buddhist monks set fire to themselves in protest at the then ruling regime. Western news media referred to these suicides as acts of “self-immolation”. In these cases, however, the manner of death is closer to martyrdom (suicide as a protest) than self-destruction (suicide as a relief).

In terms of the chief feature of self-destruction, immolation implies physical loss of life, either slowly or quickly, as a way to eliminate the conflict. For example, one person might drink himself to death over the course of a decade, while another might simply slash his wrists.

According to World Health Organization (WHO) estimates, in the year 2000, approximately one million people died from suicide, and 10 to 20 times more people attempted suicide worldwide. This represents one death every 40 seconds and one attempt every 3 seconds, on average. Suicide is now one of the three leading causes of death among young people. More people around the world are now dying from suicide than from armed conflict.

The majority of suicides occur in a context of psychological upheaval or crisis. In 90% of cases of actual suicide, a mental disorder prior to the event such as major depression can be identified. Studies of children and adolescents who commit suicide have found not only show a strong prevalence of stressful life events combined with mental disorder (depression, bipolar) but also a level of antisocial behaviour (unwillingness to comply with normal rules) and often an excessive consumption of alcohol or other drugs. In other words, suicide is more likely when a self-destructive tendency is reinforced or enabled through intoxication.

Handling Self-Destruction

As with every negative character feature, the key to handling self-destruction is becoming conscious of how it operates in oneself. Begin with the mask or persona:

- Do I try to get others to perceive me as carefree, wild, crazy?

- Do I tend to take risks and act recklessly more than others?

Try to catch yourself in the act of putting on your “devil-may-care” mask or whatever it is for you.

Then dig deeper:

- Underneath that outer facade, am I really trying to keep everything under control?

- It’s like I constantly need to prove that I am in total control. Why do I do this? What am I afraid of?

- Why do I sometimes feel like I’d be better off dead? Is there some part of me that is unbeable or unacceptable?

- What do I fear would happen if I opened up to this “other” me?

- Do I just wish others could see, understand and accept the pain I am in?

Approaching the deepest level you may need outside help in the form of a counsellor, therapist or at least a close friend, perhaps even a psychiatrist, especially if you are tackling memories of abuse:

- Where does this fear come from?

- How was I hurt?

Just as you can become more aware of self-destructiveness through personal observation and self-enquiry, so too you can gain more control over it through that awareness and by exercising choice in the moment.

- Whenever I am tempted to harm myself, I can ask myself what message I am trying to send to others. Then I can look for ways to convey that message more explicitly and skilfully.

Another way to handle a dominant negative trait (chief feature) is to “slide” to the positive pole of its opposite. When caught in the grip of immolation or suicide, the negative pole of self-destruction, balance can be found in the positive pole of greed, namely egoism, desire or appetite. In other words, you give attention to what you actually need or want, and communicate that to others.

Further Reading

Read our article on A comprehensive approach to understanding suicide and its prevention.

| For an excellent book about the various negative patterns and how to handle them, see Transforming Your Dragons by José Stevens. | |

| Another great book about the seven character flaws, recently translated from the original German: The Seven Archetypes of Fear, by Varda Hasselmann and Frank Schmolke. |

At Positive Psychology and Educational Consult, we are ready to help you to navigate your life. Contact us today. We are available online 24/7.

Phone: +2348034105253. Email: positivepsychologyorgng@gmail.com twitter: @positiv92592869. facebook: positive.psych.12

Great wordpress blog here.. It’s hard to find quality writing like yours these days. I really appreciate people like you! take care

Thanks very much. We borrow other people’s wisdom to make things better.

I really like your writing style, great info, thanks for putting up :D. “In every affair consider what precedes and what follows, and then undertake it.” by Epictetus.

Perfectly written subject matter, regards for selective information. “You can do very little with faith, but you can do nothing without it.” by Samuel Butler.

I keep listening to the newscast talk about receiving boundless online grant applications so I have been looking around for the best site to get one. Could you tell me please, where could i get some?