For centuries, musicians have used drugs to enhance creativity, and listeners have used drugs to heighten the pleasure created by music. And the two riff off each other, endlessly. The relationship between drugs and music is also reflected in lyrics and in the way these lyrics were composed by musicians, some of whom were undoubtedly influenced by the copious amounts of heroin, cocaine, and “reefer” they consumed, as their songs sometimes reveal.

Acid rock would never have happened without LSD, and house music, with its repetitive 4/4 beats, would have remained a niche musical taste if it weren’t for the wide availability of MDMA (ecstasy, molly) in the 1980s and 1990s. And don’t be fooled by country music’s wholesome name. Country songs make more references to drugs than any other genre of popular music, including hip hop.

Pairing Drugs and Music

Certain styles of music match the effects of certain drugs. Amphetamine, for example, is often matched with fast, repetitive music, as it provides stimulation, enabling people to dance quickly. MDMA’s (ecstasy) tendency to produce repetitive movement and feelings of pleasure through movement and dance is also well known.

There is a rich representation of drugs in popular music, and although studies have shown higher levels of drug use in listeners of some genres of music, the relationship is complex. Drug representations may serve to normalise use for some listeners, but drugs and music are powerful ways of strengthening social bonds. They both provide an identity and a sense of connection between people. Music and drugs can bring together people in a political way, too, as the response to attempts to close down illegal raves showed.

Whether it’s booze (writers), heroin (rock stars), or cocaine (anyone with money), we’ve long associated, and romanticized the link between, intoxicants and artists’ careers, songs, novels, and films. The definitive heroin movie, for example — Trainspotting? Pulp Fiction? The Basketball Diaries? — is the familiar stuff of barstool debates.

What we haven’t done is reckon with an ascendant crop of pharmaceuticals — some legal, some semi-legal, some illegal — that are now routinely referenced in works of art. From Xanax to Adderall to Percocet to the codeine-cough-syrup concoction “lean,” there’s a medicine cabinet’s worth of drugs that are influencing, inspiring, beguiling, and, in some cases, destroying artists. We may have a good sense of the artistic reputation of, say, booze — from its effects (getting drunk) to its notable laureates (Cheever), but what is the artistic connotation of lean? It’s worth asking, given that 33 percent of the rap songs that reached the top ten of Billboard’s “Hot 100” chart in 2017 mentioned this drug. Here, we attempt to decipher the cultural meaning of a new generation of intoxicants, alongside a few familiar mainstays.

Adderall

May induce: Mental endurance, enhanced concentration, increased focus.

Also known as: Beans, study buddies.

Status: Prescription.

Backstory: A combination of amphetamine and dextroamphetamine, Adderall is a rebranded version of Obetrol, which had its FDA approval as a weight-loss drug withdrawn back in 1973. Although Adderall is marketed as a treatment for children’s ADHD, by the mid-aughts, adults had become the fastest-growing group using the drug.

Cultural connotations: While Adderall, which spikes dopamine levels, can induce euphoria, it’s primarily prized for its reputed capacity to increase mental focus. As such, it’s typically associated not with recreation but persistence and ambition. The writer Tao Lin has confessed to “taking Adderall and staying up all day and night” while writing. In hip-hop, Detroit rapper Danny Brown refers to himself as the Adderall Admiral, calling the drug “like steroids in the rap game.”

Notable laureates: “My thing is Adderall,” Brown told Complex magazine in 2012. “That’s really just a working thing. If I’m doing shows and I wanna stay up, I take Adderall … Every time I write some shit on Addy, … it’s like words come together crazy.” In one song, Brown raps: “Eatin’ on an Adderall / Wash it down with alcohol / Writin’ holy mackerel / Actual or factual.”

Alcohol

May induce: Relaxation, reduced inhibitions, delusions of literary grandeur.

Also known as: Booze, juice, hooch, sauce.

Status: Legal.

Backstory: This product of fermented grains dates back to at least 7,000 B.C.

Cultural connotations: Despite its reputation as a party-starter, alcohol works chemically as a depressant, impairing brain functions such as judgment, self-criticism, and inhibition. Which is probably why booze has always been a writer’s vice, from Ernest Hemingway (“I have drunk since I was 15, and few things have given me more pleasure”) to Marguerite Duras (“I’m a real writer. I was a real alcoholic”) to Stephen King (“I never understood social drinking, that’s always seemed to me like kissing your sister”).

Notable laureates: Choose one. How about William Faulkner? Dorothy Parker? Christopher Hitchens? As for the poet of hangovers, it’s hard to top this description from Lucky Jim, by Kingsley Amis: “His mouth had been used as a latrine by some small creature of the night, and then as its mausoleum.”

Cocaine

May induce: Euphoria, mental alertness, hyperactivity, hypersensitivity.

Also known as: Coke, blow, toot, nose candy, Bolivian marching powder.

Status: Illegal.

Backstory: Peruvians have long chewed coca leaves as part of cultural traditions. Now, cocaine consists of processed coca leaves in the form of a white crystal powder.

Cultural connotations: Coke stimulates the release of dopamine, causing a short but intense high that leaves a fierce craving for more. In pop culture (as in life), it’s most often associated with greed, materialism, and money, or all three — in other words, Wall Street. Then, of course, there’s music: As Steven Tyler of Aerosmith said on 60 Minutes, “You could also say I’ve snorted half of Peru. It’s what we did.” Similarly, the figure of the crack-and-coke-dealing kingpin emerged as a staple of early-’90s hip-hop, from Jay-Z, who went from drug dealer to mogul, to Pusha T of Clipse, who rapped, “I move ’caine like a cripple / Balance weight through the hood / Kids call me Mr. Sniffles.” As with anything, however, drug references (and drugs themselves) wax and wane in their cultural prominence; in recent years, anti-anxiety drugs (see Xanax) and codeine-based concoctions (see Lean) have superseded cocaine as the rap referent of choice.

Notable laureates: From the opening paragraph of Jay McInerney’s Bright Lights, Big City: “Somewhere back there you could have cut your losses, but you rode past that moment on a comet trail of white powder and now you are trying to hang on to the rush.”

Lean (Codeine)

May induce: Mild euphoria, lethargy, a sensation of disassociation with the body.

Also known as: Sizzurp, purple drank, dirty Sprite.

Status: Codeine is prescription only.

Backstory: Lean is a homemade concoction of codeine (as contained in cough medicines), Sprite, and Jolly Ranchers, typically sipped out of a double-stacked Styrofoam cup.

Cultural connotations: Lean came to prominence in the early ’90s thanks to Houston rappers such as Pimp C of UGK (who later died from complications caused by drinking it) and DJ Screw — who invented “chopped and screwed” music, in which he remixed albums to the slowed-down rate of about 60 beats per minute, which linked up perfectly with the super-mellow state of mind that results from drinking lean. As the influence of Houston’s rap scene grew, so did the popularity of the drink. When Lil Wayne came to national prominence, he brought lean with him.

Notable laureates: Three 6 Mafia, the group from Memphis that went on to win an Oscar, famously rapped about “Sippin’ on some sizzurp.” More recently, it’s been popularized by rappers from Atlanta, like Gucci Mane (World War 3: Lean, “Servin’ Lean”); Future, who frequently sings and raps about drug binges (“Codeine Crazy,” “Dirty Sprite”); and Young Thug (“Drinking Lean Is Amazing” and “2 Cups Stuffed,” in which he raps, “Lean! Lean, lean! Lean! Lean, lean, lean!”).

Ecstasy and Molly

May induce: Euphoria, feelings of enhanced empathy.

Also known as: E, X, disco biscuits, Scooby snacks.

Status: Illegal.

Backstory: Ecstasy’s chemical name is 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, often shortened to MDMA. MDMA was first administered in the U.S. as a psychotherapy treatment in the ’70s, but a group of Ivy League chemists (and former Timothy Leary associates) introduced E into the dance and party scene experimentally, pitching it to users as a healthier alternative to cocaine. Molly is a resurgent form of ecstasy that commonly comes in powder or crystal form.

Cultural connotations: In the 1990s, ecstasy fueled club kids, club kids fueled ecstasy, and the drug became entwined with outlets like the Limelight in New York and Warehouse in Chicago, where house music was born. Molly is essentially the second coming of ecstasy, gaining popularity with the rise of EDM in the late aughts and early 2010s and the growth of festivals like Electric Daisy Carnival in Las Vegas, Electric Zoo in New York, and Ultra in Miami, where in 2012 Madonna notoriously asked the crowd, “How many people in this crowd have seen Molly?”

Notable laureates: In 1996, Scottish novelist Irvine Welsh released his best seller Ecstasy: Three Tales of Chemical Romance. And in 2013, Molly went pop when former Disney star Miley Cyrus sang, on “We Can’t Stop,” “So la da da di / We like to party / dancing with Molly / Doing whatever we want.”

Fentanyl

May induce: Euphoria, relaxation.

Also known as: Fent.

Status: Prescription.

Backstory: Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid that is similar to morphine but up to 100 times more potent. In 2017, it was linked to more overdoses than any other synthetic opioid.

Cultural connotations: With fentanyl, it’s less about what it does than about who it’s taken away. This already dangerously potent and addictive painkiller is often illicitly manufactured in clandestine labs and sold as knockoff Xanax or other prescription pills. It’s also been linked to nearly every recent celebrity overdose, including Prince, Tom Petty, and, reportedly, Dolores O’Riordan, though her autopsy results are still pending.

Notable laureates: Usually, by the time we hear about someone’s fentanyl use, it’s too late. For lyrical references, though, there’s this, from Black Thought’s recent freestyle on Hot 97: “As babies we went from Similac and Enfamil / To the internet and fentanyl.”

Heroin

May induce: A rush of euphoria described in Trainspotting as like “the best orgasm you ever had, multipl[ied] by a thousand, and you’re still nowhere near it.”

Also known as: Smack, horse, dope, skag, junk.

Status: Illegal.

Backstory: Opium cultivation from poppies dates back to ancient civilizations. Morphine was derived from opium by 1805, and heroin was synthesized from morphine by an English chemist in 1874.

Cultural connotations: Heroin is closely associated with jazz giants — such as Miles Davis, John Coltrane, and Charlie Parker — and rock stars, specifically those involved in the Seattle grunge scene that exploded into the mainstream in the ’90s.

Notable laureates: From Trainspotting, again: “I chose not to choose life. I chose somethin’ else. And the reasons? There are no reasons. Who needs reasons when you’ve got heroin?”

LSD

May induce: Hallucinations, perceptual distortions, an outsize sense of one’s cognitive abilities.

Also known as: Acid.

Status: Illegal.

Backstory: Albert Hofmann, a Swiss chemist, synthesized LSD in 1938.

Cultural connotations: Back in a different, mid-20th-century version of San Francisco, mind-expanding psychedelics fueled the ’60s counterculture movement. (Jimi Hendrix was rumored to put a tab on the inside of his bandanna during concerts and sweat it into his system.) Now, in San Francisco, a tech bro might take about one-tenth of an average dose before work, called “microdosing,” in hopes of increasing productivity. The writer Ayelet Waldman chronicled the positive effects of microdosing in her book A Really Good Day: How Microdosing Made a Mega Difference in My Mood, My Marriage, and My Life.

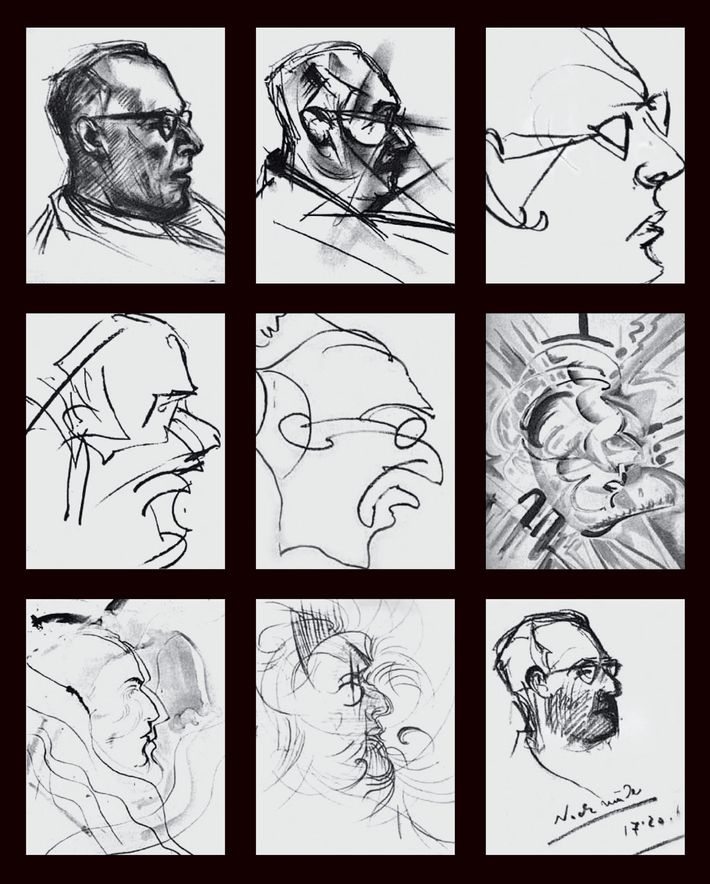

The sketches above are from an experiment believed to have been conducted circa 1954 by the psychiatrist Oscar Janiger. In the experiment, an artist was given two 50 microgram doses of LSD, separated by an hour, and asked to draw several sketches of the doctor who administered the drug over the course of eight hours.

Notable laureates: That would have to be Hunter S. Thompson. From Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: “Buy the ticket, take the ride … and if it occasionally gets a little heavier than what you had in mind, well … maybe chalk it up to forced consciousness expansion: Tune in, freak out, get beaten.”

Marijuana

May induce: Minor euphoria, heightened sensory perception, increased appetite.

Also known as: Pot, weed, chronic, Devil’s lettuce.

Status: Depends where you live.

Backstory: Cultivated for centuries across various civilizations.

Cultural connotations: Take your pick: There’s the enlightened Bob Marley, the blissed-out Willie Nelson, or the couch-bound, giggling slacker. For example: The guy who gets super-high and goes to his last-ever house party (Seth Rogen in This Is the End); the guy who gets super-high while discussing a possible shmashmortion (Seth Rogen in Knocked Up); the bored process server who happens to witness a murder (Seth Rogen in Pineapple Express); or the alien on the run from the government (Seth Rogen in Paul). It is perhaps too soon to gauge how the recent legalization of recreational weed in several states, most recently Vermont, will affect the cultural cachet of marijuana, or the career of Seth Rogen.

Notable laureates: We’ll give this one to Snoop Dogg, who counts among his various odes such titles as “Smoke the Weed,” “This Weed Iz Mine,” “Stoner’s Anthem,” and “Smokin’ Smokin’ Weed.”

OxyContin

May induce: Euphoria.

Also known as: Oxy, hillbilly heroin.

Status: Prescription.

Backstory: The synthetic opioid oxycodone was first derived from an opium alkaloid in 1916. In 1996, OxyContin, a pharmaceutical derivative, was hailed as a medical breakthrough for its potential as a long-lasting painkiller; it turned into one of the most widely used recreational opioids in America, fueling the current epidemic.

Cultural connotations: Eminem is an admitted user and has rapped about taking “enough OxyContin to send a fuckin’ ox to rehab.” In January, the photographer Nan Goldin opened up about her addiction to the pill, which she was first prescribed for wrist pain three years ago; she went from taking three a day to 18 before graduating to heroin and fentanyl and then finally going to rehab. She’s since created a foundation targeting the Sackler family, who are major art patrons and the descendants of the OxyContin developers at Purdue Pharma.

Notable laureates: California rapper Schoolboy Q has a song called “Oxy Music”: “Satan in your soul, let it take control / OxyContin fiends keep the foil low / Let the pill burn inhale, exhale it slow / Let your heart explode drop ya to the floor.”

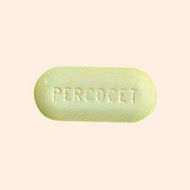

Percocet

May induce: Euphoria, numbness.

Also known as: Percs, blue dynamite.

Status: Prescription.

Backstory: Percocet is the brand name for a combination of Oxycodone and acetaminophen.

Cultural connotations: Percocet has become a favorite reference in rap music, in part because its reputation as a painkiller evokes a DGAF attitude: Pop a Perc, drink some alcohol, get happy, black out. The rapper Future elevated Perc-worship to a new status in the chorus of his hit “Mask Off,” which consists in part of the recitation “Percocets, Molly, Percocets.”

Notable laureates: In “The Percocet & Stripper Joint,” Future raps, “Bonafide superstar I’m straight up out the hood / I just did a dose of Percocet with some strippers / I just poured this lean in my cup like it’s liquor.”

Quaaludes

May induce: Deep relaxation.

Also known as: Ludes, lemons.

Status: Prescription; no longer manufactured in the United States.

Backstory: “Quaalude” was the brand name for methaqualone, a sedative that increases activity in the gaba receptors in the brain, leading to a drop in blood pressure and pulse rate. It was originally prescribed in the U.S. for insomnia but was outlawed in 1984 because of the prevalence of recreational abuse.

Cultural connotations: In his memoir, Keith Richards tells of a speedboat he bought in 1971 while living on the French Riviera and recording Exile on Main St. He named the boat Mandrax, which was the brand name for Quaaludes in England. Frank Zappa and David Bowie were also avowed fans.

Notable laureates: From the 1981 Social Distortion song “Lude Boy”: “I’m on the 714, cause I got a brand-new jar / Lemons put some light in my life, keep me happy through the night.” Quaaludes also play a featured role in one of the most memorable scenes in The Wolf of Wall Street.

Vicodin

May induce: Mild euphoria.

Also known as: Vikes, fluff, scratch.

Status: Prescription.

Backstory: Another prescription opioid, Vicodin is a mixture of hydrocodone and acetaminophen and is less potent than Percocet.

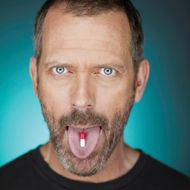

Cultural connotations: Despite the drug’s lower potency and relative lack of street cred, there’s something about its pleasurable effects and, presumably, the way the word Vicodin sounds — the harsh V followed by that strong c — that has made it a favorite reference for rappers. It’s another avowed indulgence for Eminem, who said in a 2011 interview with Complex, “Drugs put holes in my brain. I seriously don’t remember shit.” (He’s said he doesn’t remember recording “Lose Yourself” or the Marshall Mathers LP at all.) Vicodin is also a central theme in the medical drama House, where the lead character, the cranky genius Dr. Gregory House, was addicted to the drug — in an apparent echo of Sherlock Holmes’s addiction to cocaine.

Notable laureates: Beyond Eminem, there’s Future again (“Oh, you done did more drugs than me? You must be hallucinating / Oh, you did more Percs than me? Then you must be hallucinating / Don’t menace over these Vicodins, you must’ve seen Satan”) and the neo-shoe-gaze band the Pains of Being Pure at Heart (“You’re taking toffee with your Vicodin / Something sweet to forget about him”).

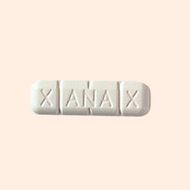

Xanax

May induce: Reduced anxiety, cognitive impairment.

Also known as: Xannies, Xan, benzos.

Status: Prescription only.

Backstory: Xanax is the trade name for alprazolam, a benzodiazepine anxiolytic commonly prescribed as a tranquilizer for anxiety and panic disorders.

Cultural connotations: Much like the connection between heroin and grunge rock, Xanax rose to prominence alongside the subgenre of emo-meets-hip-hop called SoundCloud rap, named for the online platform favored by its most prominent artists. Because of the way it reduces tension, restlessness, paranoia, and anxiety, “popping a Xan” has become the signifier of choice for disillusioned musicians checking out of a disappointing world or attempting to transform the hellscape of reality into something more bearable — so much so that SoundCloud rap is also referred to as “sad rap” or “Xanax rap.”

Notable laureates: If you have “Lil” in your name, there’s a good chance you’ve embraced Xanax: Lil Pump, who marked reaching 1 million Instagram followers with a Xanax-shaped cake; the rapper Lil Xan; and Lil Uzi Vert, who’s featured on the song “Xanax and Percocet.” Another rapper, Lil Peep, died of a fentanyl-tainted-Xanax overdose in November. On the day of his death, he filmed himself saying, “El Paso, I took six Xanax and now it’s lit. I’m good. I’m not sick. I’ma see y’all tonight.” His passing caused Lil Uzi Vert to tweet: “We Would love 2 stop … But Do You Really Care Cause We Been On Xanax All Fucking Year.” At the start of 2018, celebration of the drug seemed to subside, with rappers announcing the end of the pill. “We leaving Xanax in 2017,” Smokepurpp tweeted. Lil Xan has since announced plans to change his name.

Music and drugs

Investigators at the Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation, studied whether young people’s substance use and aggressive behaviors was related to listening to music containing messages of substance use and violence. The data was collected by using self-administered questionnaires from a sample of community college students aged 15–25. Results showed that, “Listening to rap music [is] significantly and positively associated with alcohol use, problematic alcohol use, illicit drug use, and aggressive behaviors…”. Additionally, “alcohol and illicit drug use were positively associated with listening to musical genres of techno and reggae”.

The correlation between substance abuse and drugs is not only found in the United States, but across the world. Researchers across Europe collaborated and examined relationships between music preferences and substance use (tobacco, alcohol, cannabis) among 18,103 fifteen-year-olds from ten European countries. Results showed that, “…across Europe, preferences for mainstream Pop and High-brow (classical and jazz) were negatively associated with substance use, while preferences for Dance (house/trance and techno/hardhouse) were associated positively with substance use”. This concludes that there is a direct relationship between choice of music and adolescent substance abuse in other regions of the world besides America.

Teenagers often fail to recognize that their music preferences may alter their values they hold on the acceptability of substance use. In addition, students who associated with the rave culture admit to struggling with psychedelic substance abuse such as LSD and psilocybin mushrooms. Researchers in the New York Department of Population Health examined rave attendees and relationships between recent use of various drugs in a representative sample of US high school seniors. Results showed that, “Rave attendees were more likely than non-attendees to report use of an illicit drug other than marijuana”.[45] Additionally, “…attendees were more likely to report more frequent use (≥6 times) of each drug”.

There are many music types and locations that may have an immediate association with drugs. For example, ” there was also a perceived association between EDM (electronic dance music) and drug culture,…”.[46] There are very heavy stigma and stereotypes surrounding music like this, mainly at the locations they are held, such as a club or concert venue. Most audience members go to a rave to listen to EDM music.

The questions of truly how many popular songs out of the total number created refer in some way to substance use as well as to what degree music referencing drug use influences real-life behavior remain open and complex topics. A mere minute reference by itself may have no effect in a listener, and a specific lyrical condemnation may push the listener against a particular drug, trigger curiosity, or simply do nothing.[2][8][21][48] The related issue of music censorship has been a matter debated for decades upon decades as well. In 1972, then Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) president Stanley Gortikov garnered notice when he remarked, “Music reflects and mirrors a society more than it molds and directs that society.” The year previous, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) had issued an official statement cautioning radio stations to exercise “reasonable judgement” before playing records that might “promote or glorify” illegal drug use. Months of First Amendment based legal wrangling immediately followed, causing FCC to backtrack. The inherent vagueness involved in trying to set up anti-drug standards, haggling about points in language, majorly complicates even non-governmental self-censorship.

Credits

Chen, Meng-Jinn; Miller, Brenda A.; Grube, Joel W.; Waiters, Elizabeth D. (May 2006). “Music, Substance Use, and Aggression”. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 67 (3): 373–381. doi:10.15288/jsa.2006.67.373. ISSN 0096-882X. PMC 5066304. PMID 16608146.

^ Bogt, Tom F.M. ter; Gabhainn, Saoirse Nic; Simons-Morton, Bruce G.; Ferreira, Mafalda; Hublet, Anne; Godeau, Emmanuelle; Kuntsche, Emmanuel; Richter, Matthias; the HBSC Risk Behavior and the HBSC (January 2, 2012). “Dance Is the New Metal: Adolescent Music Preferences and Substance Use Across Europe”. Substance Use & Misuse. 47 (2): 130–142. doi:10.3109/10826084.2012.637438. ISSN 1082-6084. PMC 4121736. PMID 22217067.

^ Jump up to:a b Palamar, Joseph J.; Griffin-Tomas, Marybec; Ompad, Danielle C. (July 2015). “Illicit drug use among rave attendees in a nationally representative sample of US high school seniors”. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 152: 24–31. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.05.002. ISSN 0376-8716. PMC 4458153. PMID 26005041.

^ Dayal, Geeta; Ferrigno, Emily (July 10, 2012). “Electronic Dance Music”. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.a2224259. ISBN 9781561592630. {{cite book}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)

^ Jump up to:a b “FCC Drugs Lyrics Case Under Fire”. Billboard. May 20, 1972. Retrieved March 1, 2016.