No matter what industry you work in, there is often scope for boosting overall performance. A great way of doing this is to identify and eliminate “bottlenecks,” or things that are holding you back.

But how do you identify these bottlenecks?

One approach is to use the Theory of Constraints (TOC). This helps you identify the most important bottleneck in your processes and systems, so that you can deal with it and improve performance.

In this article, we’ll explore the Theory of Constraints, and we’ll look at how you can apply it to your own situation.

Understanding the Theory

You’ve likely heard the adage, “A chain is only as strong as its weakest link,” and this is what the Theory of Constraints reflects. It was created by Dr Eli Goldratt and was published in his 1984 book “The Goal.” [1]

According to Goldratt, constraints control organizational performance. These are restrictions that prevent an organization from maximizing its performance and reaching its goals. Constraints can involve people, supplies, information, equipment, or even policies, and can be internal or external to an organization.

The theory says that every system, no matter how well it performs, has at least one constraint that limits its performance – this is the system’s “weakest link.” The theory also says that a system can have only one constraint at a time, and that other areas of weakness are “non-constraints” until they become the weakest link.

You use the theory by identifying your constraint and changing the way that you work so that you can overcome it.

The theory was originally used successfully in manufacturing, but you can use it in a variety of situations. It’s most useful with very important or frequently-used processes within your organization.

The Theory of Constraints is a methodology for identifying the most important limiting factor (i.e., constraint) that stands in the way of achieving a goal and then systematically improving that constraint until it is no longer the limiting factor. In manufacturing, the constraint is often referred to as a bottleneck.

The Theory of Constraints takes a scientific approach to improvement. It hypothesizes that every complex system, including manufacturing processes, consists of multiple linked activities, one of which acts as a constraint upon the entire system (i.e., the constraint activity is the “weakest link in the chain”).

So what is the ultimate goal of most manufacturing companies? To make a profit – both in the short term and in the long term. The Theory of Constraints provides a powerful set of tools for helping to achieve that goal, including:

- The Five Focusing Steps: a methodology for identifying and eliminating constraints

- The Thinking Processes: tools for analyzing and resolving problems

- Throughput Accounting: a method for measuring performance and guiding management decisions

Dr. Eliyahu Goldratt conceived the Theory of Constraints (TOC), and introduced it to a wide audience through his bestselling 1984 novel, “The Goal”. Since then, TOC has continued to evolve and develop, and today it is a significant factor within the world of management best practices.

One of the appealing characteristics of the Theory of Constraints is that it inherently prioritizes improvement activities. The top priority is always the current constraint. In environments where there is an urgent need to improve, TOC offers a highly focused methodology for creating rapid improvement.

A successful Theory of Constraints implementation will have the following benefits:

- Increased Profit: the primary goal of TOC for most companies

- Fast Improvement: a result of focusing all attention on one critical area – the system constraint

- Improved Capacity: optimizing the constraint enables more product to be manufactured

- Reduced Lead Times: optimizing the constraint results in smoother and faster product flow

- Reduced Inventory: eliminating bottlenecks means there will be less work-in-process.

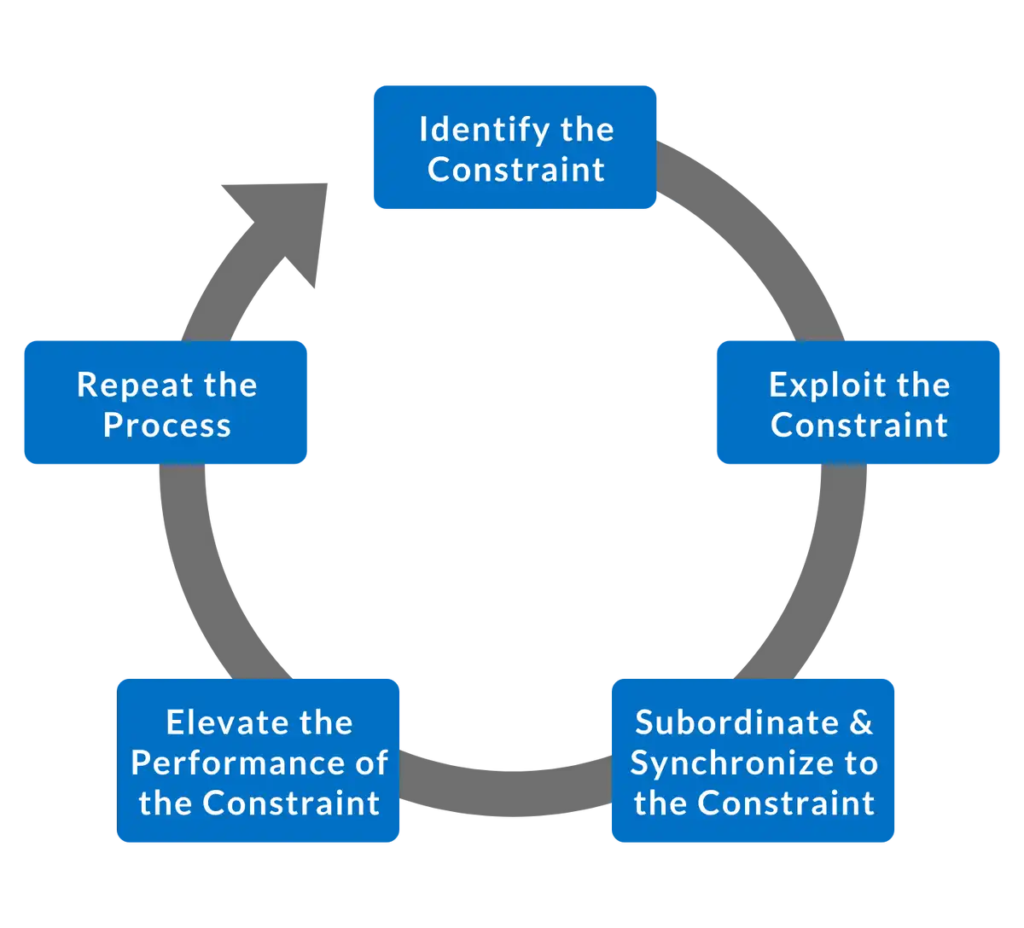

The Theory of Constraints uses a process known as the Five Focusing Steps to identify and eliminate constraints (i.e., bottlenecks).

Applying the Theory

Let’s look at a step-by-step process for using the theory:

Step 1: Identify the Constraint

The first step is to identify your weakest link – this is the factor that’s holding you back the most.

Start by looking at the processes that you use regularly. Are you working as efficiently as you could be, or are there bottlenecks – for example, because your people lack skills or training, or because you lack capacity in a key area?

Here, it can help to use tools like Flow Charts, Swim Lane Diagrams, Storyboarding, and Failure Modes and Effects Analysis to map out your processes and identify what’s causing issues. You can also brainstorm constraints with team members, and use tools like the 5 Whys Technique and Root Cause Analysis to identify possible issues.

Remember that constraints may not just be physical. They can also include intangible factors such as ineffective communication, restrictive company policies, or even poor team morale.

Also bear in mind that, according to the theory, a system can only have one constraint at a time. So, you need to decide which factor is your weakest link, and focus on that. If this isn’t obvious, use tools like Pareto Analysis to identify the constraint.

Step 2: Manage the Constraint

Once you’ve identified the constraint, you need to figure out how to manage it. What can you do to increase efficiency in this area and cure the problem? (Goldratt calls this “exploiting the constraint.”)

Your solutions will vary depending on your team, your goals, and the constraint you’re trying to overcome. For example, it might involve helping a team member delegate work effectively, modifying lunch breaks or vacation time to make workflow more efficient, or reorganizing the way that a task is done to make it more efficient.

Here, it’s useful to review approaches used in Lean Manufacturing, Kanban, Kaizen, and the 5S System to see if these can help you manage your constraint.

Again, you’ll also find it useful to brainstorm possible solutions with people in your team, and to use problem-solving tools such as the Five Whys and Cause and Effect Analysis to identify the real issues behind complex problems.

Step 3: Evaluate Performance

Finally, look at how your constraint is performing with the fixes you’ve put into place. Is it working well? Or is it still holding back the performance of the rest of the system?

If the constraint is still negatively affecting performance, move back to step 2. If you’ve dealt with the constraint effectively, you can move back to step 1 and identify another constraint.

Note:

Remember that the theory says that every process has at least one constraint. While this may be true, be sensible in how you apply the theory – sometimes removing this constraint will have a minimal impact on performance.

Key Points

Dr Eli Goldratt developed his Theory of Constraints in his 1984 book “The Goal.”

The theory says that every system, no matter how well it performs, has at least one constraint that limits its performance. You use the theory by identifying your constraint and restructuring the way that you work so that you can overcome it.

You can minimize constraints and work more efficiently toward accomplishing your goals by working through these steps:

- Identify the constraint.

- Manage the constraint.

- Evaluate performance.

Be sensible in how you apply the theory – sometimes the effort required to fix a constraint might not be worth the improvement in performance.

THE NATURE OF CONSTRAINTS

What are Constraints?

Constraints are anything that prevents the organization from making progress towards its goal. In manufacturing processes, constraints are often referred to as bottlenecks. Interestingly, constraints can take many forms other than equipment. There are differing opinions on how to best categorize constraints; a common approach is shown in the following table.

| Constraint | Description |

|---|---|

| Physical | Typically equipment, but can also be other tangible items, such as material shortages, lack of people, or lack of space. |

| Policy | Required or recommended ways of working. May be informal (e.g., described to new employees as “how things are done here”). Examples include company procedures (e.g., how lot sizes are calculated, bonus plans, overtime policy), union contracts (e.g., a contract that prohibits cross-training), or government regulations (e.g., mandated breaks). |

| Paradigm | Deeply engrained beliefs or habits. For example, the belief that “we must always keep our equipment running to lower the manufacturing cost per piece”. A close relative of the policy constraint. |

| Market | Occurs when production capacity exceeds sales (the external marketplace is constraining throughput). If there is an effective ongoing application of the Theory of Constraints, eventually the constraint is likely to move to the marketplace. |

There are also differing opinions on whether a system can have more than one constraint. The conventional wisdom is that most systems have one constraint, and occasionally a system may have two or three constraints.

In manufacturing plants where a mix of products is produced, it is possible for each product to take a unique manufacturing path and the constraint may “move” depending on the path taken. This environment can be modeled as multiple systems – one for each unique manufacturing path.

Policy Constraints

Policy constraints deserve special mention. It may come as a surprise that the most common form of constraint (by far) is the policy constraint.

Since policy constraints often stem from long-established and widely accepted policies, they can be particularly difficult to identify and even harder to overcome. It is typically much easier for an external party to identify policy constraints, since an external party is less likely to take existing policies for granted.

When a policy constraint is associated with a firmly entrenched paradigm (e.g., “we must always keep our equipment running to lower the manufacturing cost per piece”), a significant investment in training and coaching is likely to be required to change the paradigm and eliminate the constraint.

Policy constraints are not addressed through application of the Five Focusing Steps. Instead, the three questions discussed earlier in the Thinking Processes section are applied:

- What needs to be changed?

- What should it be changed to?

- What actions will cause the change?

The Thinking Processes are designed to effectively work through these questions and resolve conflicts that may arise from changing existing policies.

References

[1] Goldratt, E.M. and Cox, J. (2004). ‘The Goal: A Process of Ongoing Improvement,’ 3rd Edition, Great Barrington: North River Press.